Verneuil-sur-Avre, one of those quiet mediaeval towns of France, is conveniently

placed for travellers taking one of the quieter routes inland from Normandy

beaches; perhaps en route for Chartres or the Loire. The town boasts the church

of St Mary Magdalene, with its dramatic tower in ‘flamboyant Gothic’ style and

the relics of its mediaeval defences; the ‘Grey Tower’ and a line of ramparts,

complete with wet ditch, on its north-western and north-eastern sides.

Verneuil’s church tower and tree-lined ramparts

Six hundred years ago, during the final decades of the Hundred Years’ War

Verneuil needed those defences. The town was at the heart of contested country;

threatened by both English and Armagnac (or Dauphinois) French forces and

often at the risk of a change of ownership.

That summer, 1424, the English forces of the Duke of Bedford, uncle of

England’s infant King Henry VI and his Regent of France, were pressing hard

their claims across that contested landscape. War in the 1420s could be harsh; the

Archbishop of Rouen’s castle at Gaillon, above the Seine, had just been battered

into submission with artillery and siege engines and selected members of its

garrison executed, but it could also be civilised and common sense.

At Ivry, some thirty miles north-east of Verneuil, the town, loyal to the Dauphin

Charles (squeezed from his throne by the English and their Burgundian allies)

had been stormed by the English. The town’s castle held out, however, and in the

words of the Burgundian chronicler, Jehan de Wavrin (who was serving alongside

the English that season) being “strong and well furnished for defence, held out a

month longer, at the end of which time the besieged made a treaty with the English promising to yield up the fortress…on the eve of the Assumption…should [they] not be succoured by King Charles.”

In the weeks leading to the Feast of the Assumption (15 August) both the Dauphin

and Duke of Bedford had made strenuous efforts to gather their armies,

apparently either to relieve or ensure the fall of Ivry. Bedford had over ten

thousand men in the field, having called up all his reserves and denuded the

English-held garrisons of Normandy. He also reached Ivry first and occupied the

best defensive ground, but Bedford awaited his foe in vain. If Ivry was to have

been a battle by appointment, it was an appointment missed by the French.

Bedford’s view of Verneuil

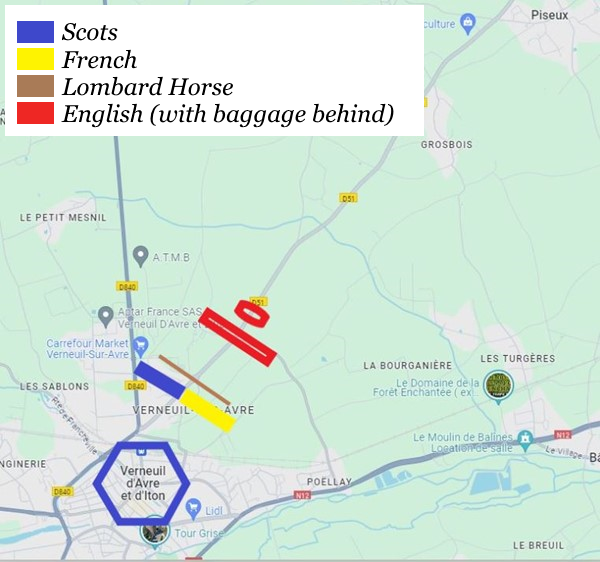

Instead, the duke of Alençon led his army, supplemented with a Scottish force

commanded by the earls of Douglas and Buchan, to Verneuil. There they terrified

the garrison into surrendering the town by declaring that the English had been

defeated; supporting their story by displaying bound and bloodied Scotsmen

before the walls who were able to impersonate English ‘captives’.

Bedford now did a curious thing – considering that his army was already

somewhat outnumbered. He divided his army, despatching a strong force of his

Burgundian allies to continue their siege of Nesle, before marching down the old

Roman road, west towards Verneuil. On 17 August 1424 Bedford’s army

emerged from the woods around Piseux to find his enemy awaiting him. As

Wavrin recalled, Bedford “beheld the town and all the force of the French

arranged and set in order of battle, which was a very fair thing to see; for without doubt I the author of this work had never seen a fairer company nor one where there were so many of the nobility as there were, nor set in better order, nor showing greater appearance of a desire to fight.”

Bedford’s army, a mixture of English, Burgundian and local troops from the

Normandy garrisons, had ridden to battle but deployed on foot. Men at Arms,

well armoured, provided the core of the force, supported by perhaps three times

the number of longbowmen. A reserve, or baggage guard, of ‘pages and varlets’

stiffened with archers, was left to the rear with the waggons and horses; the

animals tied together in pairs either for added protection or to form a greater

obstacle.

Across the road to Verneuil, the French and Scots formed one continuous ‘battle’

or division, their front protected by a screen of horsemen. These were a mass

heavily armoured Lombard horsemen, hired mercenaries, supported by lighter-armed Gascons – whose aim was to crash through the flanks of Bedford’s army,

attacking the longbowmen there, before sweeping around to capture the baggage

park and attack the English rear.

“At the onset there was great noise and great shouting…” remembered Wavrin,

and “…the archers of England and the Scots…began to shoot one against the

other so murderously that it was a horror to look upon…After…the opponents

attacked each very furiously, hand to hand…the blood of the slain stretched upon

the ground, and that of the wounded ran in great streams…This battle lasted

about three quarters of an hour, very terrible and sanguinary…”

A composite view of the battlefield of Verneuil (looking north)

Presumably heavily engaged in the thick of the infantry combat, Wavrin recalled

little of the cavalry action. The Lombards and Gascons attacked and penetrated

the English baggage park but seem to have been either driven off or satisfied

themselves with looting; leaving their Scots and French allies to fight it out on

the plain.

The battle was a bloody one. Bedford’s men-at-arms, wielding pole-axes, lances

and swords, seem to have slowly yet effectively cut their way through their

enemy, until, finally, their ranks broke and a slaughter of fleeing Scots and

Dauphinois French began; turning the fields of Verneuil into the bloody meadow

Wavrin remembered and filling the town ditch red.

A contemporary journal, kept in Paris, declared that the Armagnac French had

been let down by “greedy cowards” amongst their hired Lombard horse. Of the

English, it was believed that three thousand had fallen (of perhaps ten thousand

involved) while almost that number of the French and Scottish nobility and

gentry were found dead upon the field. Their dead included the counts of

Aumale, Tonnoire and Ventadour as well as the Scotch earls of Douglas and

Buchan. The losses amongst the common soldiery probably easily doubled the

number of aristocratic dead.

Though barely marked, the battlefield is easily found. There is a convenient

Carrefour supermarket and two of the dusty local roads, the Rue Jean

d’Harcourt (named for the count of Aumale) and Allée des Écossais recall the

fallen of 1424. There is a display on the battle in Verneuil’s ‘Grey Tower’.

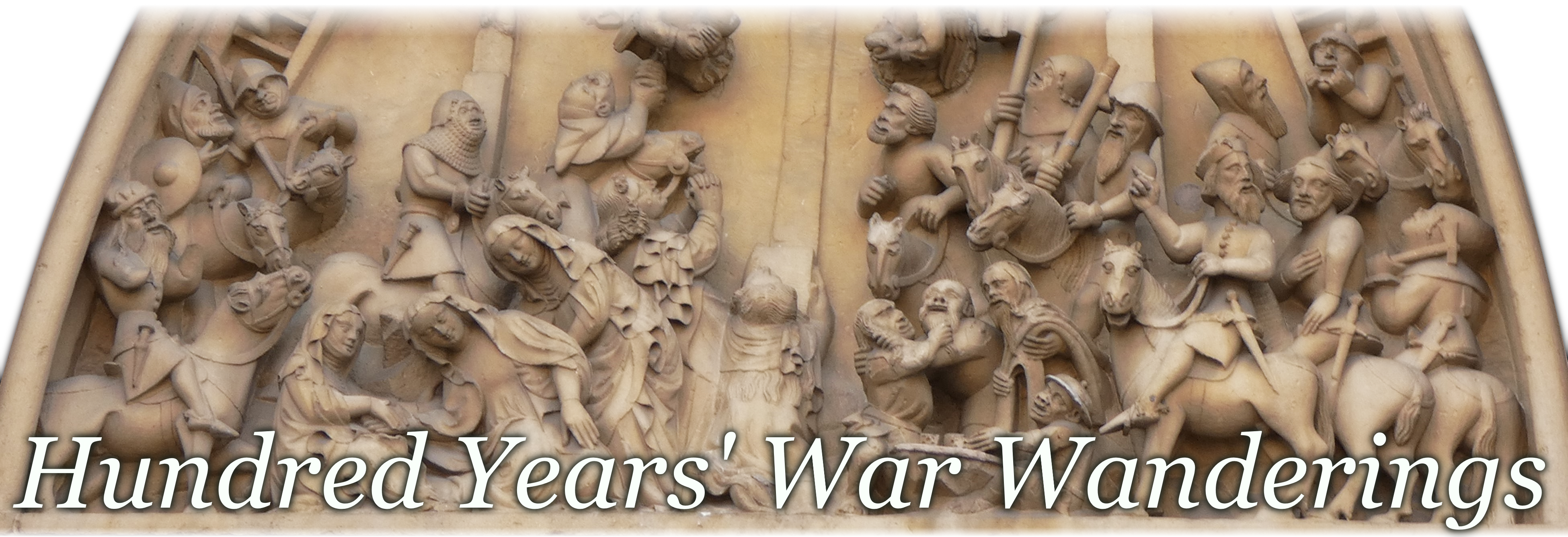

A depiction of the battle drawn about fifty years after the battle but capturing, at

least, many of its elements; the mixture of horse and foot combat, the archery

and hand-to-hand fighting.