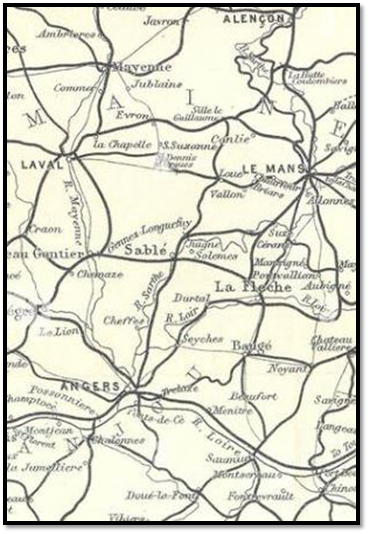

Despite its remoteness, being somewhat off the modern motorway routes, we have twice visited Baugé. In fact, as a glance at any older road map will confirm, Baugé was very much on the old road network, being a cross-roads on the north-south route across the Loire and also east-west, by way of Orleans and Angers. Good roads and river crossings were ever vital, in peace and war.

We were in search of the neighbouring village of Le Vieil-Baugé however, which was the scene of a minor but undoubtedly significant clash between the English and their Franco-Scottish enemies on Easter Saturday, 22 March 1421.

Le Vieil-Baugé lies in Anjou, which in the 1420s was very much contested territory, as roving bands of soldiers often crossed and clashed in the lands between Angers, Orleans and Le Mans. In the spring of 1421, Henry V’s brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, had led an expedition (perhaps 4,000 strong) through Maine and into Anjou. Not being burdened with a siege train, Clarence skirted the Dauphinois strongholds at Le Mans and Angers and halted, perhaps to celebrate Easter, at the castle of Beaufort-en-Vallée.

It was there that Clarence learned of the proximity of a strong Franco-Scottish army at Baugé, not ten miles to the north-west. Both the English and French armies, presumably anticipating the customary cessation of hostilities until after Easter, were widely dispersed, at rest or foraging for food. Clarence himself was at his dinner, when some Scottish prisoners, apparently brought in by English foragers and thrust before the assembled diners for questioning, let slip how close and how vulnerable their comrades were.

The Duke of Clarence seems barely to have hesitated, abandoning his dinner to gallop off up the road to Baugé in pursuit of his enemy. Often dismissed as a hot-head, brushing aside the wiser counsel of his retinue to wait and gather his troops, Clarence has been judged harshly in the light of events. However, it is also fair to recollect how many battles have been lost, or their full benefit gone unrealised, because of a hesitant or cautious general.

The D60 in 2023, up which the Duke of Clarence’s horsemen galloped towards Baugé.

At Baugé the English men at arms and comparatively few archers who could be gathered in time, probably no more than 1,200 or 1,500 men between them, crashed into a small party of French and Scots. There was a stiff fight at the River Couasnon bridge and an exchange of arrows between English longbowmen and some Scots who sought shelter in the tower of the parish church.

Clarence was in search of the enemy’s main force, however, and he led his personal retinue on, skirting Baugé, to turn south again towards the village of Vieil-Baugé. There, deployed on the low ridge up which the D61 now climbs, were John Stewart, Earl of Buchan, and the Marshal of France, Gilbert de la Fayette with some four or five thousand troops.

A view from the ridge overlooking Baugé.

It seems likely that Clarence and his men at arms barely hesitated, crashing into the press of the Franco-Scottish. The result was hardly a surprise; the Duke, easily recognisable from his helm’s jewelled coronet, was an early casualty. With him fell Sir Gilbert Umfraville, John Lord Roos and Sir John Grey, lord of Tankerville. The earls of Somerset and Huntingdon were unhorsed and captured, while at least a thousand, probably more, of the English were cut down as they attempted to flee the field.

The scene of this final, bloody climax is readily identified from a well-sited street sign, which proclaims ‘Rue de Bataille’. Our first visit to Le Vieil-Baugé was hampered by torrential rain, which made the (then vain) search for other memorials to the battle both irksome and fruitless. A second visit, however, in 2024, was an altogether sunnier and more productive.

Battle tourists ascending the ridge should press on into Vieil-Baugé. The church, with its curiously twisted spire, is worth visiting and on its churchyard wall is a slate tablet celebrating the valour of the French and Scots and, as is often the case, omitting any mention of the vanquished, save for a reference to Sir John Carmichael, who (it claims) broke his lance unhorsing the unfortunate Duke of Clarence.

A stroll beyond the church, down the hill towards the D60, will bring the battlefield tourist to a small field in which there is a public toilet (always useful) and, rather more significantly, a crop of monuments to the battle. There is an old stone with a fanciful inscription, rather hard to decipher now, and the supposed imprint of Clarence’s horseshoe. More interesting are the newer panels, dating from the 600th anniversary of the battle, which give a bi-lingual account of the engagement.

There are other memorials to recall the events of 22 March 1421 somewhat further afield. Visitors to Canterbury Cathedral will find the tomb of Clarence himself, beside his wife and her first husband, the duke depicted in the armour of a generation after his death.

On that melancholy day in 1421, the French and Scottish victors appear not to have tarried long on the battlefield and English reinforcements, including Clarence’s bastard son, found the corpses of the noble dead piled onto a cart. Eventually, their bones reached England for interment; John Lord Roos’s tomb being set up in Belvoir Priory, though it was moved at the Dissolution of the monasteries to Bottesford parish church in Leicestershire.

The effigy of John, Lord Roos of Helmsley, who died with the Duke of Clarence at Baugé. Here is the armour of an English man at arms from the later Hundred Years’ War, carefully reproduced by the alabastermen of Chellaston, even to the inscription ‘Jesus Nazareth’ upon his helm.